Empty cart

No products in the cart.

Return to Shop

Gifts for Kids

Make kids’ dreams come true with personalized gifts that ignite their imagination. Whether it’s a birthday, holiday, or just because, our custom prints add a whimsical and personal touch to every gift. Explore our selection and find the perfect way to delight and inspire the little ones in your life.

Showing 1–24 of 62 results

See

“Baby’s First Christmas” Stuffed Animals with Tee

$27.37Created to put ear-to-ear smiles on any child, these stuffed animals come with a playful attitude and customizable tees. Each plushie is 8″ tall, features polyester and plastic pellet stuffing, while their tees are 100% cotton. Perfect for ages 3+. Available animals: Panda, Lion, Bear, Bunny, Jaguar, and Sheep. .: Toy: Cotton and polyester blend […]

“Colorful Artic Animals” Kindergarten Poster

$22.00 – $30.00Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

“Colorful Cute Unicorn” Kids Mug

$15.50 – $16.50 Dark Blue Dark green Golden Yellow Green Orange Pink Black Blue Red Yellow+8Show more

Product Details:

• Ceramic

• 11 oz mug dimensions: 3.79″ (9.6 cm) in height, 3.25″ (8.3 cm) in diameter

• 15 oz mug dimensions: 4.69″ (11.9 cm) in height, 3.35″ (8.5 cm) in diameter

• Colored rim, inside, and handle

• Dishwasher and microwave safe

“Colorful Farm Animals” Kindergarten Poster

$22.00 – $30.00Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

“Colorful Forest Animals” Kindergarten Poster

$22.00 – $30.00Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

“Colorful Ocean Animals” Kindergarten Poster

$22.00 – $30.00Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

“Colorful Reptiles Animals” Kindergarten Poster

$22.00 – $30.00Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

“Colorful Zoo Animals” Kindergarten Poster

$22.00 – $30.00Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

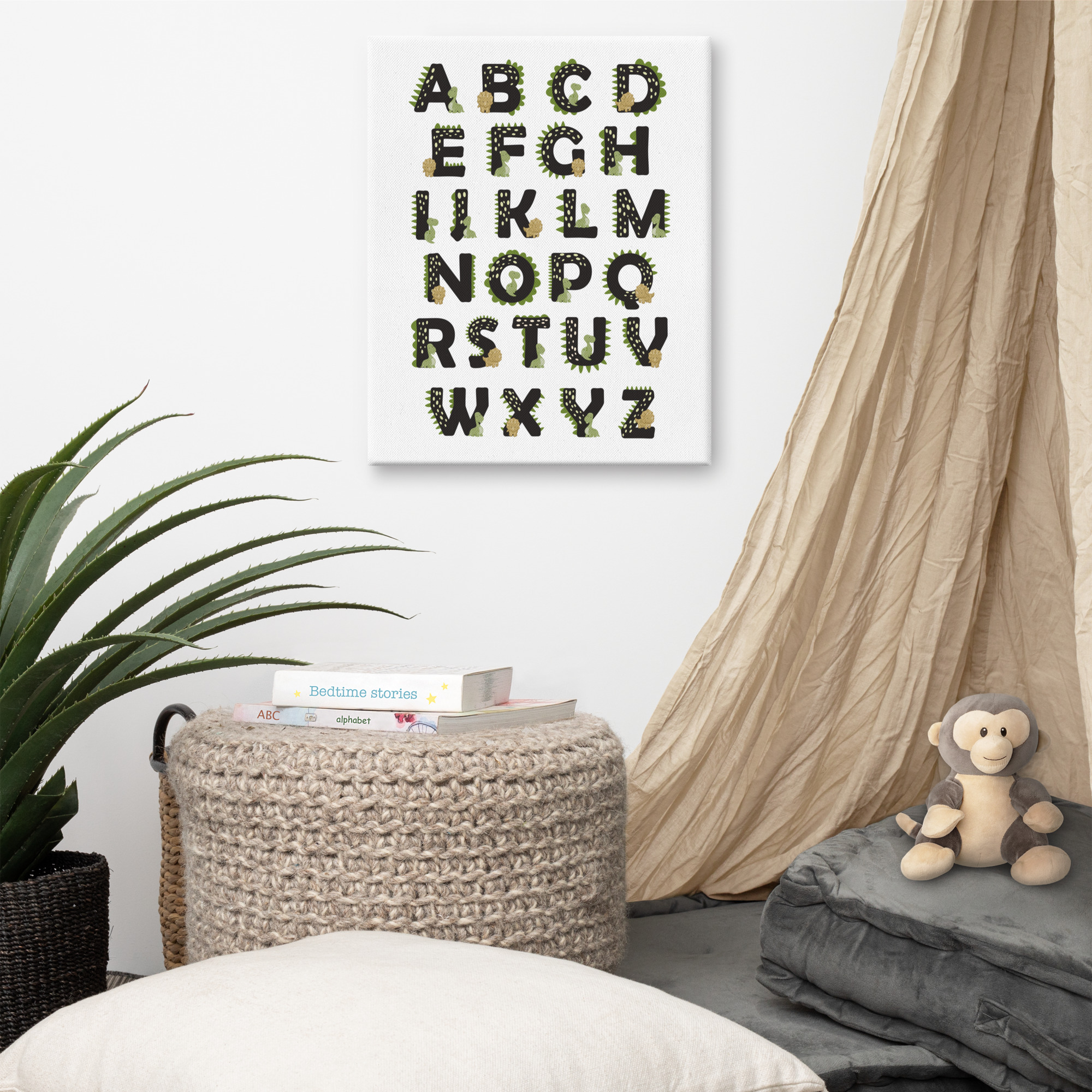

“Dinosaur Alphabet” Nursery Canvas Print

$50.50 – $104.00Product Details:

• Acid-free, PH-neutral, poly-cotton base

• 20.5 mil (0.5 mm) thick poly-cotton blend canvas

• Canvas fabric weight: 13.9 oz/yd2(470 g/m²)

• Fade-resistant

• Hand-stretched over solid wood stretcher bars

• Matte finish coating

• 1.5″ (3.81 cm) deep

• Mounting brackets included

“Dinosaur Alphabet” Nursery Framed Poster

$32.00 – $125.00 Red Oak Black White+1Show more

Product Details:

• Ayous wood .75″ (1.9 cm) thick frame from renewable forests

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil (0.26 mm)

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Lightweight

• Acrylite front protector

• Hanging hardware included

“Dream Big Little One” Nursery Framed Poster

$46.50 – $124.50 Red Oak Black White+1Show more

Product Details:

• Ayous wood .75″ (1.9 cm) thick frame from renewable forests

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil (0.26 mm)

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Lightweight

• Acrylite front protector

• Hanging hardware included

“Dream Big” Nursery Framed Poster

$31.50 – $124.00 Red Oak Black White+1Show more

Presenting the “Dream Big” Nursery Framed Poster, an exquisite addition to our collection of Nursery Framed Posters. This piece is more than just a decorative element; it’s a source of inspiration and a sophisticated addition to your child’s nursery, combining the elegance of nursery art prints with the timeless message of aspiration and hope. The […]

“Dream Big” Nursery Framed Poster

$31.50 – $124.00 Red Oak Black White+1Show more

Product Details:

• Ayous wood .75″ (1.9 cm) thick frame from renewable forests

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil (0.26 mm)

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Lightweight

• Acrylite front protector

• Hanging hardware included

“Dream Big” Nursery Poster

$9.50 – $30.50Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

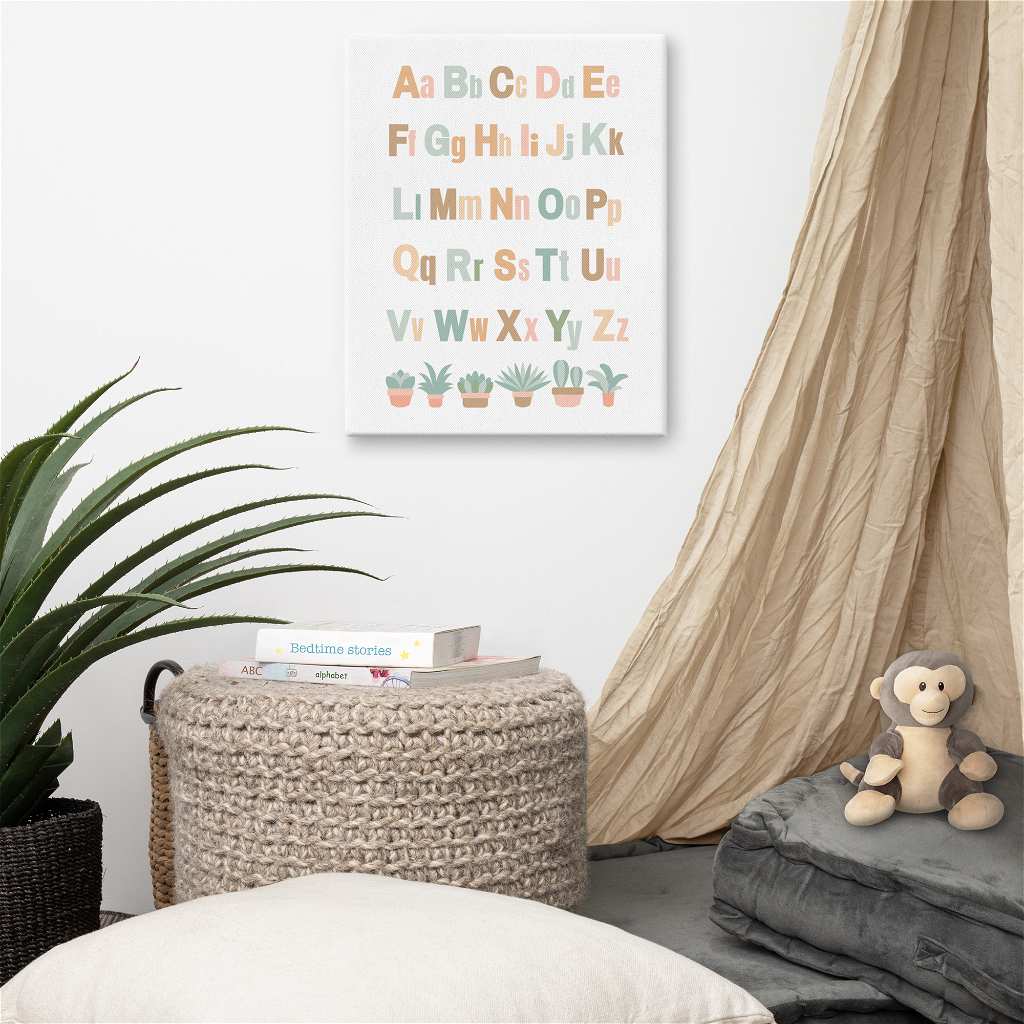

“Educational Alphabet” Nursery Canvas Print

$50.50 – $104.00Product Details:

• Acid-free, PH-neutral, poly-cotton base

• 20.5 mil (0.5 mm) thick poly-cotton blend canvas

• Canvas fabric weight: 13.9 oz/yd2(470 g/m²)

• Fade-resistant

• Hand-stretched over solid wood stretcher bars

• Matte finish coating

• 1.5″ (3.81 cm) deep

• Mounting brackets included

“Educational Alphabet” Nursery Framed Poster

$32.00 – $125.00 Red Oak Black White+1Show more

Product Details:

• Ayous wood .75″ (1.9 cm) thick frame from renewable forests

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil (0.26 mm)

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Lightweight

• Acrylite front protector

• Hanging hardware included

“Hey You” Nursery Framed Poster

$31.50 – $124.00 Red Oak Black White+1Show more

Product Details:

• Ayous wood .75″ (1.9 cm) thick frame from renewable forests

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil (0.26 mm)

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Lightweight

• Acrylite front protector

• Hanging hardware included

“Hey You” Nursery Poster

$9.50 – $30.50Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

“It’s my first Christmas!” Stuffed Animals with Tee

$36.49Product Details:

• Toy: Cotton and polyester blend

• Stuffing: Polyester fiber and plastic pellets

• T-shirt: 100% Cotton

• Sewn-in label

• For ages 3+

• Animals: Panda, Lion, Bear, Bunny, Jaguar, and Sheep

“Oh Milk” Toddler Long Sleeve Tee

$32.40 – $35.98Product Details:

• 100% combed, ring-spun cotton (fiber content may vary for different colors)

• Light fabric (4.5 oz/yd² (153 g/m²))

• Toddler unisex fit

• Tear away label

“Pastel Magic Unicorn” Nursery Framed Poster

$31.50 – $124.00 Red Oak Black White+1Show more

Product Details:

• Ayous wood .75″ (1.9 cm) thick frame from renewable forests

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil (0.26 mm)

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Lightweight

• Acrylite front protector

• Hanging hardware included

“Pastel Magic Unicorn” Nursery Poster

$9.50 – $30.50Product Details:

• Paper thickness: 10.3 mil

• Paper weight: 189 g/m²

• Opacity: 94%

• ISO brightness: 104%

“Santa’s Favorite” Stuffed Animals with Tee

$27.37Created to put ear-to-ear smiles on any child, these stuffed animals come with a playful attitude and customizable tees. Each plushie is 8″ tall, features polyester and plastic pellet stuffing, while their tees are 100% cotton. Perfect for ages 3+. Available animals: Panda, Lion, Bear, Bunny, Jaguar, and Sheep. .: Toy: Cotton and polyester blend […]

“Solar System” Nursery Canvas Print

$50.50 – $104.00Product Details:

• Acid-free, PH-neutral, poly-cotton base

• 20.5 mil (0.5 mm) thick poly-cotton blend canvas

• Canvas fabric weight: 13.9 oz/yd2(470 g/m²)

• Fade-resistant

• Hand-stretched over solid wood stretcher bars

• Matte finish coating

• 1.5″ (3.81 cm) deep

• Mounting brackets included